Sparkling wine

Sparkling Wine | Effervescent Wines from Around the World

From Spanish Cava to Italian Prosecco, the Crémants of France and South African Cap Classique, sparkling wine is produced in every major wine region of the world, in a variety of colours, varieties and styles. Whether you’re looking for a classic, tried-and-true Champagne or a New World sparkler from California, that widely beloved “Pop” and steam of effervescence are sure to add a special sparkle to any moment of celebration. Discover the story of these bubbly wines, how they came to be, how they are made and the many forms they take around the globe.

The Origin and Spread of Sparkling Wine

While effervescence in wine has been observed throughout the history of wine production, it was actually considered a fault in most regions until the late 17th century. It was originally the British who first recognised bubbles in a wine as a pleasant feature, one which made for a lighter body and textural intrigue on the palate. In the 17th century, the British began producing glass in coal-fuelled ovens which proved more durable than French glass produced by wood fire. In the winter months in Champagne region of France, the cold temperatures would sometimes cause the fermentation process to stop, leaving behind dormant yeast and residual sugar. After the wines were shipped to England, they would be bottled in this new type of durable glass and stopped with a cork. And when the temperatures began to rise in the spring, fermentation inside the bottles would restart, producing carbon dioxide gas trapped inside. Unwillingly, the English merchants had created sparkling Champagne wines before producers from Champagne even caught on to the trend. Over time, the demand for sparkling wine in England and, eventually, Paris led producers in Champagne to shift their focus on the production of effervescent cuvées. The great Maisons du Champagne established in the 19th century would continue to perfect their process of sparkling wine production - named the “methode champenoise” (Champagne method) or “methode traditionelle” (traditional method) - throughout the decades that followed.

Eventually, the sparkling wine trend spread throughout Europe. In the 1860’s Joseph Raventos from the town of Sant Sadurni de Noya in the Penedes region of Catalonia travelled to France in hopes of selling the wines of his family winery, Codorniu. In Champagne, he learned about the process of sparkling wine production and decided to recreate it back home but with three white grapes: Macabeo, Xarel·lo and Parellada. Raventos released his first “méthode champenoise” sparkling wine in 1872. Inspired by its success, he gathered fellow winemakers of the region to discuss and share ideas about sparkling wine. They renamed their product Cava to differentiate it.

In the Veneto region of north-eastern Italy, a sparkling wine produced from the native Glera grape by the Charmat method became increasingly popular around the same time. Once considered the “poor man’s Champagne,” Prosecco continued to evolve in quality and today this category includes many of the finest sparkling wines. Eventually, in the 1950’s the “methode champenoise” was adopted to produce high-quality Italian sparkling wines in the Franciacorta area of Italy’s Lombardy region. In the late 1960’s, the method also spread to South Africa, where it became known as “Methode Cap Classique.” In the United States, this method was first used by the Korbal brothers in 1892 to produce the best quality sparkling wines (then called “California champagne”) in the Russian River Valley of Sonoma County, California. Today, sparkling wine is produced in almost every wine region in the world, from a variety of grape varieties and terroirs.

How Sparkling Wine is Produced

The production of sparkling wine begins in much the same way as the production of still wines, but with some significant differences. The viticultural processes are largely similar, except that grapes destined for sparkling wines are often harvested early, when the acid levels are still quite high and when tannins and phenolic compounds are not yet fully developed. For the most part, the grapes are quickly pressed and separated from their skins in order to keep maceration between the juice and skins at a minimum, (except in the case of some rosé sparkling wines and Blanc de Noirs “white from red” wines, for which some skin contact is allowed). Primary fermentation takes place like with most still wines, though the yeasts chosen will be specially cultivated for sparkling wine production. Malolactic fermentation may or may not take place, depending on the style desired. Following fermentation, the base wines are blended to form a cuvée. Unlike in the case of still wines, sparkling wines are usually a blend of several different varieties, plots and vintages. There are exceptions, of course, including single-varietal sparkling wines (like the 100% Chardonnay Blanc de Blancs), single-vineyard cuvées and single-vintage sparkling wine.

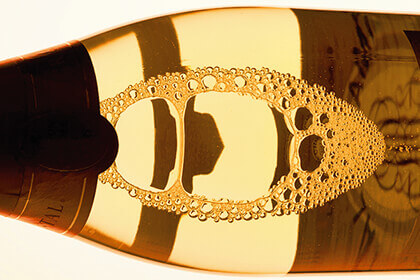

It is the next step in the winemaking process, that of secondary fermentation, that really sets sparkling wines apart from still wines and introduces variety among them. During this second fermentation stage, the carbon dioxide released by the metabolisation of sugars by yeasts is retained and dissolved into the wine to create a high pressure (of around 5 atmospheres) in the bottle, resulting in the formation of bubbles when the bottle is opened and the wine poured in the glass. There are several methods for carrying out secondary fermentation, the three most common of which are the traditional method, transfer method and Charmat method.

The so-called “traditional method,” believed to originate in Champagne and therefore also called “méthode champenoise” or “Champagne method) involves bottling the already blended base cuvee with a mixture of sugar, yeast and nutrients for the yeast (the addition of which is called tirage). The yeast metabolises the sugar and lets out carbon dioxide which gets trapped inside the bottle. The dead yeast cells (or lees) that result from secondary fermentation are sometimes left in the bottle so that the wine aged sur lie, developing a certain maturity of flavour and a rich texture. The process of eventually removing the lees begins with riddling, or turning the bottles neck downwards and around in different angles in order to move the lees to the neck if the bottle. Next, the bottle necks are cooled to a temperature at which the precipitation freezes and when the temporary crown cap is removed and the bottles opened, this precipitate is pushed out by the pressure inside of the bottle. This process is called disgorging. Before being stopped with a Champagne cork, the bottle is refilled with a liqueur d’expedition to replace the missing volume and at this point a “dosage” of sugar may be added as well. Champagne, Cremant sparkling wines from other regions of France, Cava and South African Cap Classique sparkling wines are produced with the traditional method.

Some sparkling wines are produced by the “methode ancestrale,” which means that disgorgement does not take place and the bottles are sold with the lees still present as sediment. These wines are sometimes called “pétillant naturel” or, more popularly “pét-nat.”

The transfer method of producing sparkling wine is similar to the traditional method in that secondary fermentation takes place in bottle. However, by this method, the individual bottles are emptied out into a large pressurised tank, where the wine is filtered and its liqueur de dosage. The wine is then filled back into bottles and corked under pressure to preserve the carbonation. This method is often used to produce large format bottles of Champagne, such as Jeroboams, or half-bottles. The transfer method is also popular in Australia and New Zealand.

The Charmat method, first developed in the 1890’s by Italian Federico Martinotti and later developed under a new patent by Eugene Charmat in 1907, is used to produce one of the world’s most popular sparkling wines, Prosecco. By this method, also known as the tank method, the wine undergoes secondary fermentation in a stainless steel pressure tank into which sugar and yeast has been added. The wine is filtered and bottled after fermentation is complete.

A Word about Dosage in Sparkling wine

The amount of sugar added in with the liquer d’expedition when the sparkling wine is disgorged determines its overall sweetness level. Originally, most sparkling Champagne wines were sweet until the British palate began demanding dryer styles and producers responded by reducing dosage. Today, sparkling wines are divided into the following categories depending on dosage:

- Doux or “Sweet” with 50 grams or more sugar added per litre.

- Demi Sec with 32 to 50 grams of sugar added per litre.

- Sec, which means “Dry” but actually has a slight sweetness still, with 17 to 32 grams of sugar added per litre.

- Extra-Sec or “Extra Dry” with 12 to 17 grams of sugar added per litre.

- Brut, the most popular style, with 6 to 12 grams of sugar added per litre.

- Extra Brut with 0 to 6 grams of sugar added per litre.

- Zero Dosage (also known as Brut Nature) with less than 3 grams of residual sugar per litre

While a sparkling wine labelled Brut or Extra Brut will pair nicely with fresh shellfish dishes, like crab or oysters, because of its high level of acidity, you might want to consider Demi Secs or Doux with a dark chocolate dessert, for example. Meanwhile Brut Nature wines with no dosage are meant to communicate the purest possible expression of terroir in the glass.

Sparkling Wines from Around the World

Sparkling wine is now produced in most major wine regions of the world. While the most prestigious of sparkling wines, no doubt, come from the Champagne region of France and are composed of some combination of Pinot Noir, Chardonnay and Pinot Meunier (known as the Champagne Blend), sparkling wines are also produced in many other areas of France. These wines are known as “cremant” (“Cremant de Loire,” “Cremant de Bourgogne” or “Cremant du Jura” for example) and tend to be less expensive than most champagne. The Loire region (and Saumur, in particular) is especially well known for Cremant production, most often made from a blend of Chardonnay, Chenin Blanc and Cabernet Franc (but with varieties like Sauvignon Blanc, Cabernet Sauvignon, Pinot Noir and Gamay allowed as well). In fact, Cremant wines come in a wide variety of styles and can be made with a wide range of grape varieties. Other French sparkling wines not labelled “Cremant” include those of Vouvray, made of 100% Chenin Blanc.

Venezia Giulia regions of north-eastern Italy from a blend of at least 85% local Glera, along with other local or international varieties, such as Pinot Blanc and Chardonnay. Some of the most acclaimed Prosecco wines comes from the hilly DOCG region of Conegliano Valdobbiadene Prosecco. Unlike Champagne, the laws of the DOC Prosecco requires Prosecco to be vinified as a white wine. Rosé sparkling wines from the same region are often labelled “Vino Spumante.” Another popular type of Italian sparkling wine is the semi-sweet, low-alcohol Moscato d’Asti wine from the Piedmont region of north-western Italy. Produced from Moscato grapes, these sparklers offer gorgeous floral fragrances on the nose, along with stone fruit and fresh grape aromas. And for something a bit more colourful, Lambrusco wines are red sparkling wines produced in the Emilia Romagna region of northern Italy. Lambrusco wines pair beautifully with a wide range of dishes (think Prosciutto di Parma or a Magherita pizza).

Cava, the iconic sparkling wine of Spain was once produced only with traditional grape varieties (Macabeo, Parellada and Xarel·lo) but Champagne varieties (Chardonnay and Pinot Noir) are today also permitted. While Macabeo makes up roughly half of most cava blends, it is the Xarel·lo that contributes the slightly earthy aromas which set Cava apart from other sparkling wines. Unlike Champagne, the appellation of DO Cava currently refers more to the style than a geographical region. While Cava was originally produced exclusively in the town of Sadurni de Noya in the Catalonia region, which still remains the heart of Cava today, the DO Cava also recognises Cava produced from Aragon, Rioja, Navarra, Extremadura and Pais Vasco. Food pairings with Cava depend largely on the ageing style, which can be divided into three categories: Cava (aged a minimum of 9 months on lees), Reserva Cava (aged a minimum of 15 months on lees) and Gran Reserva Cava (aged a minimum of 30 months on lees). While the fresh flavours of less-aged Cava make it the ideal pairing with dishes like ceviche or grilled fish, the toasty and nutty aromas of Reserva and Gran Reserva Cava will allow these to pair with more indulgent dishes, like buttered lobster claw or juicy crab cakes.

Sparkling wine is also produced by both traditional and Charmat methods in the United States, particularly in California and in the Finger Lakes region of New York State. While the first American sparkling wines were made from Riesling, Traminer, Chasselas and Muscatel, these varieties were gradually replaced with Chardonnay, Pinot Noir, Pinot Meunier and Pinot Blanc in the blend. In the past few decades many of the most prestigious Champagne Houses have invested in California sparkling wines, including Domaine Chandon by Moet et Chandon, Roederer Estate by Louis Roederer and Domaine Carneros by Taittinger. Historically, American producers have had the legal right to label their sparkling wines as “Champagne.” This changed in 2006, when the United States and the European Union signed a wine-trade agreement, which included an agreement on the part of the Americans not to use “Champagne” on their wine labels, except on previously approved labels. Depending on sweetness and ageing, American sparkling wines will pair beautifully to a wide range of dishes, from smoked salmon blinis to a Thanksgiving turkey with cranberry sauce. Buy these for your next family dinner! Delicious!